© 2008-2024 Musica Inspirata

Inspired Music

bagpipe construction

Medieval Muse Information

Approaching the study of bagpipes used in the medieval period, I believe the topic should be introduced with an important observation.

At the current state of research, no reconstruction of these instruments can be proposed with a sufficient degree of reliability.

This limitation is due to the fact that no material remains have been found to date. Unfortunately, archaeologists and researchers have not been able to obtain either fragments of bagpipes dating back to the era, nor, even less, complete instruments to study, measure, and reproduce.

A primary cause of this absolute lack of archaeological sources is to be found in the extreme perishability of wood and leather, the main materials used for the construction of these instruments. Only in very rare cases has the particular nature of some soils in northern Europe allowed a small number of wind instruments to reach us. This is the case, for example, of some recorders, dated around the 14th century and found in excellent condition in Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Estonia.

A second hypothesis to justify the absence of finds from the period can easily be ascribed to cultural reasons: most likely, the enormous changes in instrumentation that took place during the Renaissance led to medieval instruments being slowly abandoned or destroyed. As possible confirmation of this hypothesis, and ironically, most of the aforementioned recorders were found during excavations of certain places of decency.

That said, not all is lost. Keeping well in mind the necessary boundaries of this research, many other sources come to our aid.

Starting from literary sources, one can gather a considerable number of poetic texts, stories, and novels where the bagpipe is mentioned unequivocally. To give just a few examples of this rich case history, one need only think of the “Jeu de Robin et Marion” composed by Adam de la Halle in the 13th century, where the bagpipe is called “muse au grant bourdon” or Boccaccio’s “Decameron” which, at the end of the sixth day, depicts Tindaro as follows:

"But the king, who was in a good mood, had Tindaro called, and ordered him to bring out his bagpipe, to the sound of which he made many dances be performed. But, as a good part of the night had already passed, he told everyone to go to sleep.”

Likewise, in the prologue to “The Canterbury Tales,” Chaucer, introducing the character of the Miller, makes explicit reference to his skill in playing the bagpipe. The fact that the author placed this instrument in the hands of such a character does not exactly fill us with pride, but the description is so delightful that one cannot help but smile.

"He was a janglere and a goliardeys,

And that was most of sinne and harlotryes.

Wel coude he stelen corn, and tolled thryes;

And yet he hadde a thombe of gold pardee.

A whyt cote and a blew hood wered he.

A baggepype wel coude he blowe and sowne,

And therwithal he broghte us out of towne.”

Translation:

"He was a chatterbox and a jolly fellow,

especially when it came to sins and obscenities

he was very capable of stealing grain and selling it at three times its price;

and yet, by God, he had a golden thumb.

He wore a white tunic and a blue hood.

He knew how to inflate and play the bagpipe well.

And to its sound he led us out of town."

These literary sources, like many others, rarely give us information about the structure and construction criteria of the instruments described, but they are extremely valuable in helping us better understand their practical use, social placement, and the musical tastes characteristic of each geographical area of Europe.

A second and fundamental type of documents that can be consulted for the reconstruction of ancient instruments is formed by the rich heritage of iconographic sources.

There are hundreds of miniatures, frescoes, and sculptures from the medieval period that depict musicians, angels, or fantastic characters intent on playing bagpipes.

Below we present some examples and you can view many more by joining the Facebook group "Iconography of the bagpipe in Italy"

"Joueur de chevrette"

Musée Saint Rémi, Reims, 13th cent.

John II of France establishes the Order of the Star

Grandes Chroniques de France, 14th century

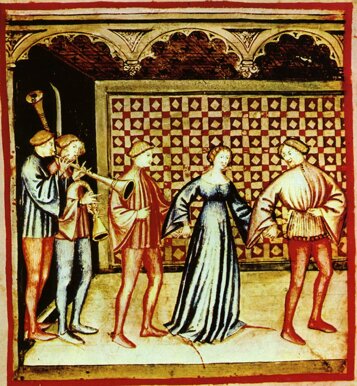

To play and to dance

Theatrum Sanitatis, 14th century

These depictions, and many others, most often achieve a good degree of precision in rendering detail and, in many cases, are of great help in confirming hypotheses and conjectures or at least in decisively discarding them.

It is certain that these images cannot in any way show us the most important and decisive part of these instruments: the boring of the pipes and the reeds mounted.

Ultimately, all these sources need to be integrated and blended with a rich wealth of information on construction tradition, musical theory, the laws of acoustics, and the history of technology.

We would like to dedicate one last mention to the name we have chosen to call our reconstruction proposals.

The term Musa is of very ancient origin and appears in one of the earliest medieval descriptions of these instruments written by the monk Johannes Cottonius.

We believe that the benevolence with which it was described, in addition to redeeming us from the legacy of Chaucer's poor Miller, is a precious guide for understanding these instruments beyond the distortions in which they are often forced.

"Dicitur autem musica, ut quidam volunt, a musa, quae est instrumentum quoddam musicae decenter satis et iocunde clangens. Sed videamus, qua ratione, qua auctoritate a musa traxerit nomen musica. Musa, ut diximus instrumentum quoddam est omnia musicae superexcellens instrumenta, quippe quae omnium vim atque modum in se continet: humano siquidem inflatur spiritu ut tibia, manu temperatur ut phiala, folle excitatur ut organa. Unde et a Graeco quod est μεση mesa, id est media, musa dicitur, eo quod sicut in aliquo medio diversa coeunt spatia, ita et in musa multimoda conveniunt instrumenta. Non ergo incongrue a principali parte sua musica nomen sortita est.”

Translation:

"As some say, music takes its name precisely from the word musa, which is an instrument most suitable for music and with a cheerful sound. Let us then see for what reason and for what merits music derives its name from the musa. The musa, as we have said, is an instrument that by far surpasses all the others since it contains within itself all their characteristics and virtues: it is set in motion by breath like the flute, the hand glides among the notes as in the vielle, and it has its air reserve in the bag like the organ. Furthermore, the term musa derives from the Greek word μεση (mese) which means center, precisely because just as in the center different directions converge, so in the musa all the virtues of the other instruments converge. Rightly, therefore, we can say that music primarily takes its name from the musa."

(Johannes Cottonius, "De Musica cum Tonario", Chapter III, ca. 1100 AD)

© 2008-2024 Musica Inspirata